Unabridged: a Charlesbridge Children's Book Blog

The Birth of Sir Cumference 0

By Cindy Neuschwander

“Math is too hard.”

“I hate math.”

“I don’t get it.”

I hear these familiar refrains from students frequently. As a former math-hater, I can sympathize. I said them all too. And I meant them. Why is it that such a beautiful, structured discipline evokes such negative reactions?

I’ve asked myself this question many times. After years of teaching and observing students, I think part of it boils down to materials. The textbook/workbook pairing is a typical delivery method in mathematics instruction in the United States. It leaves little leeway for inserting outside materials. Teachers can feel constrained and uninspired by these one-size-fits all programs. And so can the kids.

As a result, too many of our students self-select out of mathematics and careers that depend upon numbers. There have been frequent school conferences where parents whisper conspiratorially to me that, “I was never very good at math, either.” But as far as I know, there is no math gene. Everyone can learn this stuff . . . and enjoy it.

What to do? Certainly there are many spices that teachers can and do throw into their instruction to make curriculum more memorable and approachable. Math literature is one of them. There’s always time in the school day to squeeze in a fun story. Why not read a one that you can also use in learning math concepts and skills? It’s been done for quite a few years with good success.

I started doing this in the late 1980s. With the guidance of a marvelous mentor, I used math stories with my second grade students. They responded very positively to them. The only challenge I had back them was the selection. There were so few books to choose from. There seemed to be one way to change that.

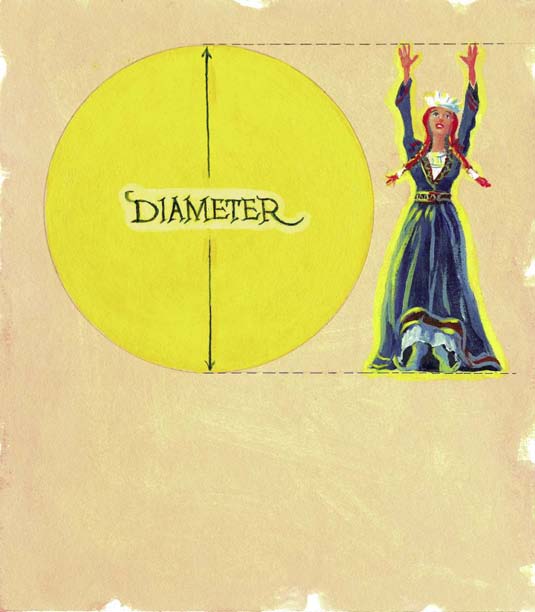

I began to write some myself. Sir Cumference was a pneumonic device that I used as a child. I could picture that knight standing around King Arthur’s Round Table. Rather than having to memorize the term from a diagram that showed the circumference, I just told myself a good story. Lady Di of Ameter and son Radius came to me later as I fleshed out a fun geometry adventure that became the beginning of the Sir Cumference Math Adventures.

While living in England in 1993 and teaching school there, the first Sir Cumference story was born. A visit to Winchester Castle was the inspiration. Hanging on a wall in the Great Hall is a round painted table top measuring 18 feet across depicting King Arthur and his knights.

“What if this was the final product of a series of tables that carpenters made for the King?” I wondered. The story gained some legs (unlike the poor table top!). I could explore a number of different shapes as well as how one shape could change into another. There was a lot of geometry there, all in a story.

I worked on the book for a couple of years, while in England and after our family returned to the United States. I took a writing class at a nearby university that helped me understand the picture book genre more clearly. I wrote and rewrote while my poor family heard more iterations of this story than any human should have to tolerate. But they graciously listened and commented.

One day my younger son rushed in after school. “Hey, Seth, how was your day?” I asked. Instead of the usual grunts, I heard an ebullient and engaged response.

“Mom, it worked!”

“What worked?” I asked.

“Your story,” he answered. “I remembered everything on my math test and got it all right.”

Confirmation based upon a sample size of one. Still, it was a good beginning. I kept rewriting until the story seemed as good as I could make it and I sent it off to publishers. Charlesbridge picked it up. The rest is history, as they say.

I’m excited to announce adventure number eleven, Sir Cumference Gets Decima’s Point. It will be available October 27, 2020. It’s a story about decimal place value with ogres and a food fight. It’s fun and memorable mathematics.

The Sir Cumference series: shameless thievery of the Arthurian legend and puns that are so bad, they’re good. Thanks for reading and using them.

Here’s a sneak peek at the cover of the newest math adventure:

- Colette Parry

The Whole Book Approach Goes Online: Tips to Enrich Storytimes During Periods of Emergency Remote Learning 0

By Megan Dowd Lambert

My book, Reading Picture Books with Children: How to Shake Up Storytime and Get Kids Talking about What They See (Charlesbridge 2015) introduced the Whole Book Approach storytime model I developed in association with The Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art to a wider audience. Now that it’s in paperback, I’m thrilled to see my book reaching even more readers, and new Whole Book Approach Storytime Sets for grades pre-k through 5 from Steps to Literacy are poised to help educators shake up storytime in the new schoolyear. Each set includes a sturdy book bin holding:

My book, Reading Picture Books with Children: How to Shake Up Storytime and Get Kids Talking about What They See (Charlesbridge 2015) introduced the Whole Book Approach storytime model I developed in association with The Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art to a wider audience. Now that it’s in paperback, I’m thrilled to see my book reaching even more readers, and new Whole Book Approach Storytime Sets for grades pre-k through 5 from Steps to Literacy are poised to help educators shake up storytime in the new schoolyear. Each set includes a sturdy book bin holding:

- 10 picture books I selected by award-winning authors and illustrators (See grade-level book lists here)

- A Whole Book Approach Storytime Guide that I wrote for each grade level, with customized discussion plans, extension activities, and resources for all 10 curated books in each bin (See a sample plan here)

- “A Message from Megan” in each Guide, which introduces the Whole Book Approach and offers additional Critical Literacy resources (See excerpts from this piece here on the Diverse BookFinder site)

- A copy of Reading Picture Books With Children

I put my whole heart into this project, and I am so excited for the sets to find their way into classrooms; and yet, my excitement is dampened by the tremendous uncertainty facing educators and families alike as the 2020/2021 academic year looms before us in the midst of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. As a parent, I’ve been searching for resources to help guide and structure my children’s experiences with emergency remote learning since school shutdowns began in our community last March. Their teachers rallied to provide online learning, and I supported, encouraged, and augmented my children’s participation as best I could. As an educator, I also began trying to provide resources to help others. I co-authored an annotated picture book list for Embrace Race, I led professional development webinars, offered online storytimes with Link to Libraries and Story Starters, and gave online interviews. Given the fact that shutdowns seem more like an inevitability than a possibility for many schools during the upcoming academic year, I’ve also done a lot of thinking about how my new Whole Book Approach Storytime Sets might be most useful during periods of emergency remote learning.

First, although the household market wasn’t the planned target audience for the sets, I hope that some families with children in preschool and elementary school will be able to purchase Whole Book Approach Storytime Sets to enrich their picture book reading at home. During the spring 2020 shutdown, booklists, activity ideas, and homeschooling advice proliferated on the internet, leaving many people (including me!) feeling overwhelmed. Although the sets could be a big financial investment for an individual family to make, each one is a one-stop resource with 10 excellent picture books and associated discussion plans and activities for each title. I imagine families reading and rereading the picture books in their bins, and then expanding on those readings with the resources and activities paired with each title. (A pie-in-the-sky dream that would require major funding would be for schools to purchase Sets for every child in a classroom to take home in the event of a shutdown. Then, children and families would have access to the same books and resources, literally putting everyone on the same page.) Ideally, the Whole Book Approach tips and tools they use with their book bin titles will also help them see other picture books they have at home with new eyes.

As for how teachers and librarians might adapt the Whole Book approach for use in online programming and teaching, it might sound paradoxical, but I actually suggest that they hold back from doing whole Whole Book Approach readings online. Every plan in every Whole Book Approach Storytime Guide is filled with questions and prompts to guide storytime discussion about the titles I chose for the sets. Rather than restating those plans here, below, I emphasize quick comparisons, connections, definitions, and observations during online readings. It’s definitely harder to keep a group’s attention and to facilitate discussion in an online forum than it is to do so in an in-person storytime. I therefore think it’s best to use online Whole Book Approach storytimes as a means of introducing vocabulary and ideas about art and design, rather than trying to have full, lengthy discussions. As children engage in these quick conversations, tell them (and any grownups at home who might be supporting their learning) to take the terms, ideas, and questions you introduce and apply them to their reading and thinking about picture books they might have at home.

Here are some tips for teachers and librarians about how to best move Whole Book Approach storytimes from being on-the-rug to being online (Since Charlesbridge is hosting this post, all examples are drawn from their titles included in the Steps To Literacy Whole Book Approach Storytime Sets):

- If you want to pre-record a storytime, check publisher guidelines about sharing recordings to avoid copyright infringement. For example, this link provides the guidelines from Charlesbridge.

-

Whether you offer a pre-recorded storytime or a live video-conference meeting in which children can voice their responses (or perhaps type them or dictate them for someone else to type into a chat function), you can integrate Whole Book Approach tools into your reading by opening with a comparative analysis of picture book trim size. For example, if the book you read has a smaller than average trim size like Grandma's Tiny House by JaNay Brown-Wood and illustrated by Priscilla Burris, hold it up next to another book with a large trim size and ask, “Why do you think the artist chose to make this book have a tiny trim size, while this one is much bigger?” After pausing for responses (in real time, or to accommodate children watching a recording) you may want to provide your own thoughts about the rationale behind these design decisions, and then proceed into the reading. When you wrap up, remind children that you started off your reading by discussing trim size and encourage them to think about this design element when they are reading at home.

Whether you offer a pre-recorded storytime or a live video-conference meeting in which children can voice their responses (or perhaps type them or dictate them for someone else to type into a chat function), you can integrate Whole Book Approach tools into your reading by opening with a comparative analysis of picture book trim size. For example, if the book you read has a smaller than average trim size like Grandma's Tiny House by JaNay Brown-Wood and illustrated by Priscilla Burris, hold it up next to another book with a large trim size and ask, “Why do you think the artist chose to make this book have a tiny trim size, while this one is much bigger?” After pausing for responses (in real time, or to accommodate children watching a recording) you may want to provide your own thoughts about the rationale behind these design decisions, and then proceed into the reading. When you wrap up, remind children that you started off your reading by discussing trim size and encourage them to think about this design element when they are reading at home.

-

Book comparisons to start storytimes also work well with a focus on picture book orientation. For example, if the picture book you are reading online has a portrait (vertical) orientation like Flying Deep: Climb Inside Deep-Sea Submersible ALVIN by Michelle Cusolito and illustrated by Nicole Wong, hold it up next to a picture book with a landscape (horizontal) orientation and ask, “Why do you think the artist chose to give this picture book a portrait orientation so it’s taller vertically, while this other book has a wider landscape layout?” Again, after pausing, perhaps provide your own thoughts about the rationale behind these design decisions, and then when you wrap up, remind children that you started off your reading by discussing orientation and encourage them to think about this design element when they are reading at home.

Book comparisons to start storytimes also work well with a focus on picture book orientation. For example, if the picture book you are reading online has a portrait (vertical) orientation like Flying Deep: Climb Inside Deep-Sea Submersible ALVIN by Michelle Cusolito and illustrated by Nicole Wong, hold it up next to a picture book with a landscape (horizontal) orientation and ask, “Why do you think the artist chose to give this picture book a portrait orientation so it’s taller vertically, while this other book has a wider landscape layout?” Again, after pausing, perhaps provide your own thoughts about the rationale behind these design decisions, and then when you wrap up, remind children that you started off your reading by discussing orientation and encourage them to think about this design element when they are reading at home.

- Or, begin with the endpapers! Tell your group (in a recording or live) that endpapers can give us clues about picture books. A very quick and easy way to demonstrate this function during an online reading is to share a picture book like my companion titles A Crow of His Own and A Kid of Their Own (illustrated by David Hyde Costello and Jessica Lanan, respectively), in which endpaper colors match the protagonist rooster, Clyde: in the first title, endpapers are green to match Clyde’s tail feathers, and in the second they are red to match his comb and wattle. Ask students, “Can you make a match between the color of the endpapers and something in the jacket art?” If you read a picture book that has illustrated endpapers, like Chris Barton and Don Tate’s Whoosh! Lonnie Johnson’s Super-Soaking Stream of Inventions, you might ask students to comment on what kinds of clues those pictures give about the story as you enter the picture book. Once again, when you wrap up your reading, remind children that you started off your reading by discussing endpapers and encourage them to think about this design element when they are reading at home.

- Another way to foster group participation in an online storytime is to invite children to have a picture book or two by their side as you begin storytime to engage in hands-on book exploration.

- First, invite students to hold up their book if it is in landscape orientation; then, switch to portrait orientation books; then see if anyone has square or shaped books.

- Next you might ask something like, “Who has a paperback book and who has hardcover?”

- Continue by prompting those with hardcovers to remove book jackets to see if the case cover underneath is the same or different.

- Or, tell them open to endpapers and share if they can make a color match between endpapers and jacket art and if so, why it’s significant.

- Or, turn to front matter pages to see if there are any illustrations there and ask for volunteers to share how they help begin the visual storytelling.

- Or ask them all to point to the gutter in a book and then teach them that the verso is on the left-hand side and the recto is the right-hand page.

Then use the hands-on time to launch into your reading of a picture book with an emphasis on one of the design or production elements your opening exercise highlighted. For example, you might decide to draw their attention to layout and the gutter by saying: “Watch how the layout of the pictures uses or accommodates the gutter in this story. Does the gutter divide characters? Unite them? What do you think about these choices?”

-

Or, instead of reading an entire picture book straight through online, tell your students you want to use a book jacket to teach them three questions they can always use to help them be excellent picture readers. Hold up a picture book with engaging jacket art like Susan Wood and Duncan Tonatiuh’s Esquivel! Space Age Sound Artist and take just a few minutes to guide students in reading the picture with questions inspired by Visual Thinking Strategies, one of the main influences behind the Whole Book Approach:

Or, instead of reading an entire picture book straight through online, tell your students you want to use a book jacket to teach them three questions they can always use to help them be excellent picture readers. Hold up a picture book with engaging jacket art like Susan Wood and Duncan Tonatiuh’s Esquivel! Space Age Sound Artist and take just a few minutes to guide students in reading the picture with questions inspired by Visual Thinking Strategies, one of the main influences behind the Whole Book Approach:

- What do you see happening in this picture? This question will ground the group in the visual and prompt them to reflect on narrative meaning in the art instead of simply listing things they see.

- What do you see that makes you say that? This question prompts evidentiary thought, inviting students to engage in metacognition, or to think about their thinking.

- What else can we find? This question invites students to dig deeper as it holds space for more than one person to offer ideas and questions.

- Again, it can be difficult to sustain a group’s attention in an online discussion, so freely use these questions to dip into reflections that will show your students how they can use the same kind of inquiry in their independent or shared reading at home. Some other open-ended questions you might like to introduce are:

- Watch the use of any frames—what happens to them? Why is this important in the visual storytelling? Are some pictures full bleeds without frames? Why do you think the artist chose that sort of layout for some pages and not for others?

- How do words and pictures work together in this book? What do pictures tell you that words do not?

- What do you notice?

- What do you wonder?

- Tell students that some picture books have different levels of text to help convey different parts of a story and invite them to reflect on typography as you read. For example:

- My picture books A Crow of His Own and A Kid of Their Own use speech balloons for some dialogue, and they also have intraiconic text, or text within pictures, in addition to the main narrative text. Ask students to pay attention to how those other kinds of text help reveal characterization.

-

Other books like Write to Me: Letters from Japanese American Children to the Librarian They Left Behind by Cynthia Grady and illustrated by Amiko Hirao include epistolary text, or letters. You could lead into reading this book by pointing out how the display type on the jacket looks like handwriting, and then turn to any pages where you see postcards or letters in the illustrations. How might children’s experience of the book change if you flip through the book and only read the letters before or after you read the book as a whole?

Other books like Write to Me: Letters from Japanese American Children to the Librarian They Left Behind by Cynthia Grady and illustrated by Amiko Hirao include epistolary text, or letters. You could lead into reading this book by pointing out how the display type on the jacket looks like handwriting, and then turn to any pages where you see postcards or letters in the illustrations. How might children’s experience of the book change if you flip through the book and only read the letters before or after you read the book as a whole? -

Other titles like We Are Grateful: Ostaliheliga by Traci Sorell and illustrated by Frané Lessac use different font colors to make certain words stand out. In this case, Cherokee words in the text are highlighted on the page and then typographical choices help showcase pronunciation guides and definitions. The Charlesbridge website page about this picture book includes recordings of the pronunciations of the Cherokee words in the text that would be ideal for sharing in an online learning environment.

Other titles like We Are Grateful: Ostaliheliga by Traci Sorell and illustrated by Frané Lessac use different font colors to make certain words stand out. In this case, Cherokee words in the text are highlighted on the page and then typographical choices help showcase pronunciation guides and definitions. The Charlesbridge website page about this picture book includes recordings of the pronunciations of the Cherokee words in the text that would be ideal for sharing in an online learning environment.

As I mentioned above, each plan in each Whole Book Approach Storytime Guide includes activity ideas and additional resources. Like the Cherokee pronunciation recordings on the Charlesbridge website, many of these extension materials would be ideal fodder for online remote learning. I hope that teachers who buy the sets for classroom use will find these parts of the plans especially helpful if they start the year in remote learning or again must shift to such arrangements.

Ideally, shared reading, whether in-person or online, can forge connections between people as we meet to engage with stories, art, and each other. I hope that the ideas I’ve presented here will help people foster such bookish connections even if the pandemic continues to keep us from gathering as we wish we could in our classrooms and libraries. I’d love to hear how readers are using the Whole Book Approach to support online storytimes, so please reach out to me at www.megandowdlambert.com, on Twitter @MDowdLambert, and on Facebook at @MeganDowdLambert.

- Colette Parry

- Tags: author news children's books guest post literacy the whole book approach

Supporting Environmental Literacy Through Children’s Literature 0

Understanding and appreciating the natural world, and our place in it, is an important goal of K-12 education. While we cannot predict all the issues the next generation will confront, we can be certain that among them will be issues related to the environment (www.enviroliteracy.org). The National Science Board’s Environmental Science and Engineering for the 21st Century report stresses the importance of improving public knowledge of environmental issues, but what exactly does environmentally literacy look like?- Donna Spurlock

- Tags: children's books

Follow Chester! Read the Author's Note 0

The year is 1947. Jackie Robinson signs a contract with the Brooklyn Dodgers. President Truman signs an Act of Congress, beginning the Cold War. India and Pakistan gain independence from the British Empire. The world is changing.

But some parts of the world are slower to change than others. Jim Crow laws in the American South require black people to use different facilities from white people, from schools and restaurants right on down to drinking fountains. They certainly don't allow black athletes to play against white athletes. Not until Harvard's football team challenges UVA's racist policies by bringing Chester Pierce to the field.

Take a sneak peek at author Gloria Respress-Churchwell's author's note to learn more:

After talking with Dr. Chester Pierce and discussing his life with him, I wrote this story. The details about Chester’s childhood, college years, how collegiate football worked, the restaurant scene, and Chester’s response to the black fans are based on actual events. I changed some details and invented the dialogue, bathroom scene, and the play called “Follow Chester” to create a sense of what it might have been like for him to travel to and play in the South while Jim Crow laws were in place.

Charles Follis, known as “The Black Cyclone,” was the first black professional football player (with the Shelby Blues from 1902 to 1906). Fritz Pollard and Bobby Marshall were the first black players in what is now the National Football League (NFL); they played in 1920. In 1933 NFL owners decided that there would be no more African American players. This lockout is attributed to George Preston Marshall, who became owner of the Boston Braves (later the Washington Redskins) in 1932. Marshall refused African American players, and he pressured the league to maintain the same policy.

A breakthrough occurred in 1946, when Cleveland’s NFL team, the Rams, moved to Los Angeles and wanted to play at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. The LA Dons, from the All-American Football Conference (AAFC), also applied. The Coliseum Commission and black sportswriters (Los Angeles Tribune sports editor Halley Harding in particular) pushed the NFL to integrate as a condition of the lease. Both the Rams and the Dons announced they would. Kenny Washington and Woody Strode signed with the Rams. In the same year, Bill Willis and Marion Motley signed and played for the Cleveland Browns.

Even though professional football was integrated, colleges in the South didn’t allow black players until the 1960s. Black students who wanted to play football usually went to historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) such as Grambling State and Jackson State.

Chester Pierce made history in 1947. UVA thought Harvard would sit Chester out and expected they wouldn’t bring him at all. There was an unwritten college-football agreement that said when integrated college football teams played schools in the South, they wouldn’t play their black players. The all-white Southern team chose a player of equal talent to sit out the game.

When Jackie Robinson broke the baseball color barrier in 1947, Harvard knew history was on their side.

An article in the Harvard Crimson said, “Virginia officials scheduled the game hoping Harvard would voluntarily exclude Pierce. But Crimson Athletic Director Bill Bingham insisted on Pierce’s participation, and Virginia relented.”

Many newspapers and magazines covered the game. Boston Globe journalist Jeremiah Murphy (who was a UVA student at the time) described a significant moment: “Chet Pierce turned and faced the segregated black crowd behind the end zone. He was about 6-feet-3 and 235 pounds. He stood there for a second and then held up his right hand and saluted the black crowd. They stood up and applauded.”

Dr. Chester Pierce always said he didn’t do anything special. I have never spoken with a humbler man, especially given all his vast accomplishments. Although Dr. Pierce passed away in September 2016, his family and I talked, and they are pleased about this book.

Dr. Pierce’s courageous story can speak to all of us: Adversity develops courage! Confidence lives in each of us! My hope is that Follow Chester! will inspire young readers to seek out additional information about Dr. Pierce and other such heroes.

Follow Chester: A College Football Team Fights Racism and Makes History

- Colette Parry